10,000 search results

(0.06 seconds)

- Fletcher-Gothic is a typeface designed by Alan Carr, showcasing a unique balance between historical gravitas and a contemporary twist. The design of Fletcher-Gothic draws its inspiration from the tra...

- Isotype - Unknown license

- Comment by cm5dzyne,

$12.00Comment is a unique yet still basic sans serif created to provide a consistent, attractive appearance in print, especially in small-to-medium sizes. - Aunque by Cloud9 Type Dept,

$45.00 - Burton's Nightmare is a captivating display font that appears as if sprung from the feverish dreams of a storyteller who dances on the edge of whimsy and the macabre. Its design pays homage to the go...

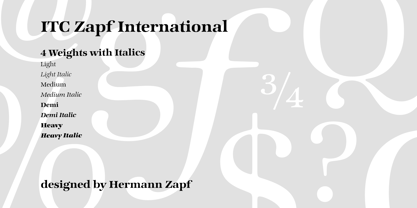

- ITC Zapf International by ITC,

$39.00Zapf International font is the work of German designer Hermann Zapf, formal enough for widespread use yet tempered with calligraphic warmth. Vigor in the italics is achieved more from design than from slant. One of the distinguishing characteristics of Zapf International is its graduation of weights. Light and medium are relatively close and equally eloquent for text. Demi is a full two steps heavier than medium and heavy several steps beyond demi. - NorB Felt Marker by NorFonts,

$28.00NorB Felt Marker is a variation of my NorB Marker font, It's handwritten text font witch you can use with any word processing program for text and display use, print and web projects, apps and ePub, comic books, graphic identities, branding, editorial, advertising, scrapbooking, cards and invitations and any casual lettering purpose… or even just for fun! It comes with 8 weights: Regular Italic Medium Medium Italic Bold Bold Italic Heavy Heavy Italic - CF Cozyscript by CozyFonts,

$25.00CF Cozyscript is an even weighted connecting script. Created in the spirit of the Old Grade School cursive chart seen above the blackboard in the front of the classroom. Giving students a constant visual reference of the smooth flow of Caps and Lower case script. Neither formal nor casual but a combination of both styles. Cozyscript is currently available in 3 styles: Light, Medium & Rounded. The Light & Medium styles are best suited for Invitations, Notes, Advertising, Personal Letters, and Sensitive Subjects such as Movie Titles, Biographies, Wedding paraphernalia, etc. The Light & Medium Glyphs finish in squared-off ends, whereas the Rounded version is slightly bolder than the Medium version with rounded ends resembling a tubular look. The Rounded version lends itself to effective use in Sports, Music, and Advertising, Graphics, Signage, Branding, Neon effects, Logos, Titles, and Packaging. With over 300 glyphs applicable in over 100 languages, Cozyscript is available for use! Cozyscript is CozyFonts Foundry's 17th Font Family released and 2nd script font by Tom (Cozy) Nikosey, California Designer. - Genial by Scholtz Fonts,

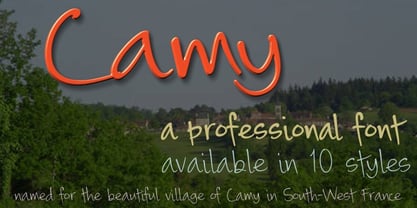

$16.95Genial is an elegant, contemporary script font in nine styles, specifically designed for maximum versatility. All of the styles, ranging from condensed thin to expanded fat, are clear and legible. The font conveys a feeling of relaxed elegance. The Family: Medium weights - Regular: of medium weight and regular width - Expanded: of medium weight and wide - Condensed: of medium weight and condensed width (narrow characters) - perfect for limited space Black weights (for best readability) - Regular: for bolder statements - Expanded: expanded width for bolder statements Light weights - Regular: regular width, delicate line - Expanded: wide characters and a delicate line - Condensed: condensed width (narrow characters) and a delicate line Fat weight - Expanded: for maximum impact (wide and extra-bold) Use a combination of styles for product branding, book covers, invitations, greeting cards. The Genial combination will enable you to use different styles of the same font for headings, sub-headings and body text. Genial contains over 250 characters - (upper and lower case characters, punctuation, numerals, symbols and accented characters are present). It has all the accented characters used in the major European languages. - Camy by Scholtz Fonts,

$9.50I wanted to create a "handwriting" font which could be used professionally. I have often needed such a font with a variety of weights and styles for a particular project and have had to resort to mixing fonts, creating a rather messy, amateur job. Camy is named for a little village in South West France where I did much of the initial work on this font. Camy is ideal for contemporary display work, comes in ten styles, and has a contemporary appeal with its casual, easy to read letters. Camy was designed as a total professional package for designers looking for a handwritten font suitable for all kinds of contemporary display work: the idea being that once you have the Camy Professional Pack you don't have to waste time searching for other handwritten fonts. The Family: LIGHT -- NARROW - light weight, condensed width, delicate line -- MEDIUM - light weight, delicate line -- WIDE - light weight, expanded width, delicate line NORMAL WEIGHT -- NARROW - of medium weight and condensed width - perfect for limited space -- MEDIUM - of medium weight -- WIDE - of medium weight and expanded width BLACK - for best readability -- NARROW - condensed width for bolder statements in small areas without losing legibility -- MEDIUM - for bolder statements -- WIDE - expanded width for bolder statements FAT -- WIDE - for maximum impact Use a combination of styles for product branding, book covers, invitations, greeting cards. The Camy combination works well for both headings and body text. Camy contains over 250 characters - (upper and lower case characters, punctuation, numerals, symbols and accented characters are present). It has all the accented characters used in the major European languages. - Filou by Volcano Type,

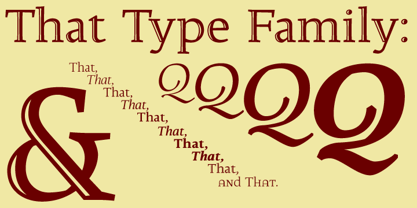

$19.00Filou is a genuine bastard inspired by three different typefaces. It consists of three weights: "Regular", "Medium" and "Extra" which can be easily mixed together. - That by Suomi,

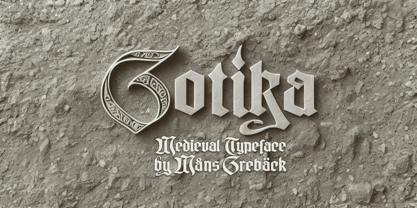

$30.00 - Gotika by Mans Greback,

$69.00Gotika, designed by Mans Greback, is a collection of blackletter fonts that masterfully blend Gothic influences with modern sensibilities. Comprising Gotika Black, Gotika Strict, and Gotika Ornament, this font family showcases the craftsmanship of calligraphy and the elegance of the medieval era. Gotika Black is a bold, street-inspired typeface, while Gotika Strict combines the historic charm of blackletter calligraphy with geometric precision. Gotika Ornament is a decorative font with Middle Ages-inspired floral designs, perfect for creating intricate and eye-catching visuals. Each font within the Gotika family is built with advanced OpenType functionality and has a guaranteed top-notch quality, containing stylistic and contextual alternates, ligatures, and more features; all to give you full control and customizability. The family has extensive lingual support, covering all Latin-based languages, from Northern Europe to South Africa, from America to South-East Asia. It contains all characters and symbols you'll ever need, including all punctuation and numbers. Mans Greback is a Swedish typeface designer, dedicated to crafting diverse and versatile fonts. With a passion for design and typography, he has developed a broad range of fonts that are utilized by designers around the world. - CorpusCare - Unknown license

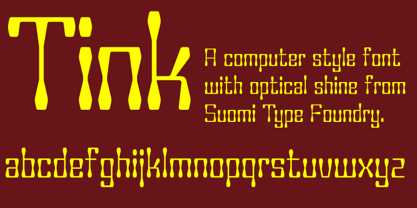

- Tink by Suomi,

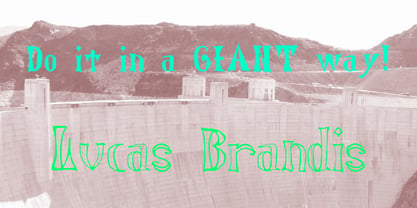

$25.00 - Lucas Brandis by Proportional Lime,

$9.99In the early days of printing everything had to be worked out from scratch. This set of lettering is based on section headings used by the Printer Lucas Brandis (no known relation), the first printer to operate in the city of Lübeck around 1473. They remind me of a medieval version of the spray paint graffiti so often seen on the sides of trains. A bit on the crude side, but also and importantly extremely noticeable. So whether you use it for creating old styled printing or some wild modern eye grabbing text item, its robust and sturdy shapes will be certain to grab the eye. - The font "WereWolf" by GautFonts is a unique and expressive typeface that truly stands out due to its thematic design and playful character. This font has been meticulously crafted to evoke the myste...

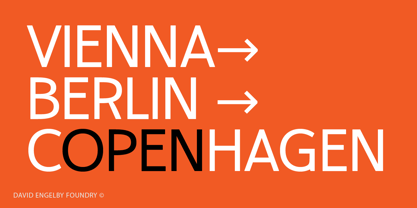

- Copenhagen Grotesk by David Engelby Foundry,

$-From Weimar to København/Copenhagen, picking up some decadent traits on its journey. The design of Copenhagen Grotesk is inspired by the great German grotesque type design history, although it will not fall into ranks in all aspects. Indeed, Copenhagen Grotesk will not be put into one single time pocket of style, so you'll notice that there's a hint of art deco style in its capital letters. The visual expression is first and foremost firmly rooted in the style of Scandinavian design, so feel free to use Copenhagen Grotesk for functional typographic design in relation to multiple media types. - Nubian by G-Type,

$39.00Nubian was one of the first typefaces ever designed by G-Type and is an elegantly proportioned, crisply modern sans serif family. Comprising five weights from Thin to Bold with true matching italics, each font also includes two sets of figures (lining and old-style numerals) and an extended European character set. Nubian has a noticeably open, semi extended appearance providing very even 'colour' and excellent legibility when set as text. The contemporary letterforms work well at all sizes in print and on screen making Nubian a great choice across all media. The family has been updated to OpenType with extended language coverage. - Benah by Twinletter,

$12.00Benah is a beautiful and exotic handwritten typeface that may be used for a variety of applications. This typeface will make your graphic look harmonious and simple, allowing you to align and maximize the appearance of your project to be the most noticeable among those accessible. This font is designed with a natural touch of handwriting which is refined to create a portion and composition that suits your needs. So this font is suitable for craft, children’s writing, adventure posters, food banner titles, wedding invitations, product packaging logos, quotes, social media page covers, furniture banner headlines, book covers, and much more. - Moyenage by Storm Type Foundry,

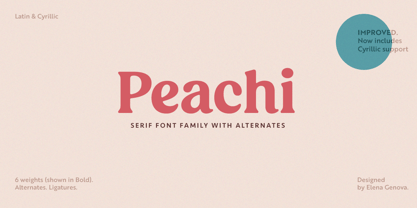

$55.00Blackletter typefaces follow certain fixed rules, both in respect to their forms and to the orthography. Possibly, they were a reaction to the half-developed Carolingian minuscule which was soon to end in the Latin script. Narrow, ordered script was to replace the round, hesitant and shattered shapes of letters in order to simplify writing, to unify the meaning of individual letters, and to save some parchment, too. Opposed to the practice common in monasterial scriptoriums where Uncial, Irish and Carolingian inspiration flew freely and as a result, the styles of writing differed in each monastery, the blackletter type was to define one, common standard. It was to express spiritual verticality, in perfect tune with the architecture of the Gothic era. Typography became an integral part of the overall style of the period. The pointed arch and the blackletter type were the vanguard of the spectacular transformation from the Middle Ages towards the modern era, they were a celebration of a time when works of art were not signed by their makers yet. Some unfortunate souls keep linking blackletter solely with Germany and the Third Reich, while the truth is that its direct predecessor, the Gothic minuscule, evolved mostly in France. Even Hitler himself indicated blackletter type obsolete in the age of steel, iron and concrete – thus making a significant contribution to the spreading of the Latin script in Germany. Once we leave our prejudice aside, we find that the shapes of blackletter type have exceptional potential, unheard of in sans-serif letterforms. The lower case letters fit into an imaginary rectangle which is easily extended both upwards and sideways. In its scope and in the name itself, the Moyenage type family project is to celebrate the diversity of the Middle Ages. I begun realizing the urge to design my own blackletter when visiting the beer gardens of Munich and while walking through the villages of rural Austria. The letters from the notice boards of inns are scented with spring air, with the flowers of cudweed, with white sausage and weissbier. The crooked calligraphic hooks and beaks seem to imitate the hearty yodeling of local drinkers and the rustle of the giant skirts of girls who distribute the giant wreaths of beer jugs. Moyenage is, however, a modern replica of blackletter, so it contains some otherwise unacceptable Latin script elements in upper case. I chose these keeping the modern reader in mind, striving for better legibility. The font is drawn as if written with a flat pen or brush, and with the ambition to, perhaps, serve as a calligraphic model. In medium width, the face is surprisingly well legible; it is perfect for menus as well as posters and CD covers for some of the heavier kinds of music. It has five types of numerals and also a set of Cyrillic script, symbolising the lovelorn union of Germans and Russians in the 20th century. Thus, it is well suited for the setting of bilingual texts of the German classic literature, which, according to the ancient rules, must not be set in Latin script. - Peachi by My Creative Land,

$25.00Peachi is a serif typeface loosely based on Morris Fuller Benton’s Souvenir forms and some other serif fonts designed in the early 1900s. It has a soft look - round corners, slightly curved legs of capital K, R, V and W; and lowercase k, v, w and y. Rather heavy ball terminals and a very large x-heigh make Peachi a perfect choice for designing titles, book covers, for branding, quotes design - basically any design that needs to make an impact and to be remembered. Peachi is released in 6 weights from Thin to Black and has stylistic alternates that make it even more versatile. While the default style follows Souvenir’s trend, the alternative style looks more modern. It’s totally up to you which style to choose for your design. To access all alternates and ligatures you’ll an OpenType aware application such as Adobe Suite or MSWord. March 2021 Update: more alternates and ligatures have been added! - Pipo by bb-bureau,

$65.00 - BB book A by bb-bureau,

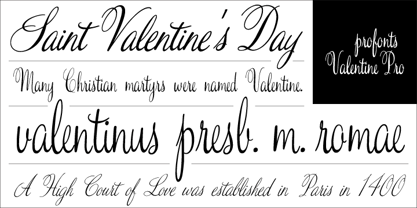

$65.00 - Valentine by profonts,

$51.99Valentine is another brand-new profonts script typeface family with versions in light, light italic, medium and medium italic, supplied in the new OpenType Pro font format. Valentine contains about 1.100 glyphs for every weight, covering the complete Latin character set (West, East, Baltic, Turkish, Romanian), and a huge number of handmade ligatures, character combinations and alternates to make it a perfect OpenType Pro connecting script. Valentine is a very distinguished, elegant and versatile script font. - Aseel by MAKYN,

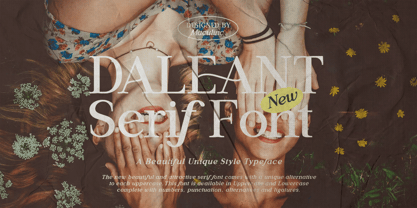

$40.00Aseel is a contemporary and legible typeface. It is intended to work well in the context of information and signage design. It also works well as a body text typeface as it is characterized by open counter forms and a large x-height. It is based on the Naskh calligraphic structure and has a medium stroke contrast. The letters are condensed to fit more information per line and it exists in three weights, regular, medium and bold. - Daleant by Maculinc,

$15.00The new beautiful and attractive Serif Font comes with a unique alternative in each Uppercase, This Font is available in Uppercase and Lowercase Complete with Numbers, Punctuation, Alternate and Ligatures. Daleant Serif Font is available in the family of Light, Light-Italic, Regular, Italic, Medium, Medium-Italic, Semi Bold, Semi Bold-Italic, Bold, Bold-Italic. Alternatives and Ligatures in this font are only available in uppercase letters, Add alternatives to make sentences more unique and interesting. - Florensans by Milan Pleva,

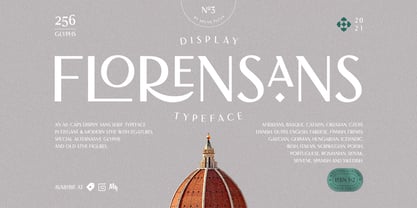

$18.00Florensans is an all caps display sans serif typeface in elegant & modern style with ligatures, special alternative glyphs and old style figures. The Florensans family contains three weights: Light, Regular and Medium. Florensans is ideal for headlines, headers, logos, labels, packaging, postcards, presentations, magazines, invitations, etc. Features: 3 Weights - Light, Regular and Medium Basic latin alphabet A-Z 64 Ligatures & Alternates 56 Accented characters Numbers, Punctuation, Currency, Symbols, Math symbols & Diacritics Old style figures Enjoy Florensans! - 3rd Man - 100% free

- Canturiana by Latinotype,

$39.00According to the Dictionary of the Spanish Royal Academy, «canturía» is the exercise of singing, and a way of singing musical compositions. Canturiana Type (derived from «canturía») has a romantic and musical air, as well as a clear sensuality thanks to its sinuous construction. The curves seduce us, conquer us, hypnotize us and the letters acquire a resounding lightness, and a very earthly presence that is complemented by a certain aerial, spiritual expressiveness. Canturiana Type is inspired by Canterbury, a font designed in the 1920s by the legendary American type designer and engineer Morris Fuller Benton and published by the American Type Founders (ATF). Canturiana Type collects all this heritage and transforms it into a digital typeface perfectly functional and adapted to the visual communication of the 21st century. Its elegant art deco essence provides it with a unique and heterodox imprint that works in very different media, giving them distinction and depth. The creative process of Canturiana Type has gone through various mutations to a point where each episode of its creation has left its mark, a multiple imprint that makes it unique, singular in its essence and plural in its possibilities. For this reason, Canturiana Type expresses itself with several voices without any variation in its essence. A conceptual ambiguity that makes it truly versatile. Canturiana Type is a typographic choir, a complex entity that has infinite nuances and tones. Classic and cool. Disruptive and romantic. Literary and musical. Canturiana Type is composed of 5 weights, and has a large number of swashes, alternate characters, ligatures and various visual elements to make compositions as titles or for use in short texts. Canturiana Type has more than a thousand glyphs and offers a wide range of languages that use the Latin alphabet. - Regrettably, as of my last update in April 2023, I don't have specific information on a font named "KING ARTHUR" designed by Maelle Keita. However, the realm of typography is a canvas for creativity,...

- Kimono Kong - Unknown license

- Abrade by J Foundry,

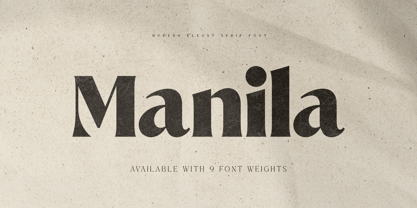

$25.00Abrade is a geometric sans serif with rational design choices for contemporary functionality. The family is designed with a medium x-height to provided great legibility in both display and text sizes. The forms are refined to work well in print and on screen. The italics maintain the rational forms, with only the essential structural changes. With 12 weights, the family is ideal for publications, digital media, corporate systems, branding, as well as your band’s gig poster. Abrade is equipped with extended language support, including Extended Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic. Features include: stylistic alternates, small caps, figure sets, and lots of OpenType features to keep designers happy. - Manila Style by Sensatype Studio,

$15.00Manila- Modern Elegant Serif Font Manila font is a modern Elegant Serif font with a Elegant , fancy, playful, unique, and versatile vintage sans serif that you can combine to get a beautiful typography. It is a Serif font with moderate contrast that perfect for branding projects, logo, wedding designs, social media posts, advertisements, product packaging, product designs, label, photography, watermark, invitation, stationery, and any projects, it makes with a high level of legibility. What's Included: Ready 9 Weight (Thin, Extralight, Light, Regular, Medium, SemiBold, Bold, ExtraBold, Black) Character set A-Z Alternative Uppercase & Lowercase Numerals & Punctuation Accented Characters (West Europe) Works on PC & Mac Wish you enjoy our font. :) - Risbeg by Craft Supply Co,

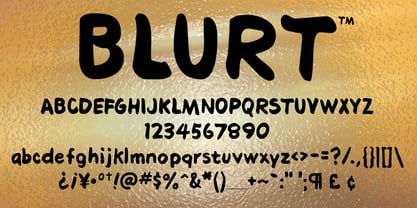

$20.00Risbeg – Elegant Serif Font: A Font for Impactful Titles Timeless Elegance Meets Modern Design Risbeg Elegant Serif Font blends classic serif features with a modern twist, creating a stylish and engaging visual experience. Its well-crafted curves and distinct serifs make it perfect for titles that demand attention. Each character in Risbeg is designed with precision, ensuring a harmonious balance in your designs. Versatile and Readable Risbeg stands out for its versatility, adapting seamlessly to various design needs. Whether it’s for branding, editorial layouts, or digital media, this font maintains readability across different mediums. Its clear, crisp lines make reading effortless, even in dense text blocks. - Blurt by Robert Petrick,

$19.95 - Rushline by Illushvara,

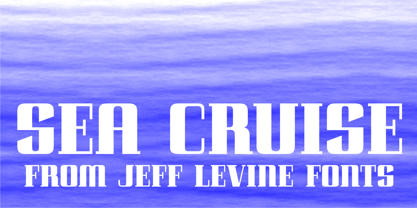

$14.00 - Sea Cruise JNL by Jeff Levine,

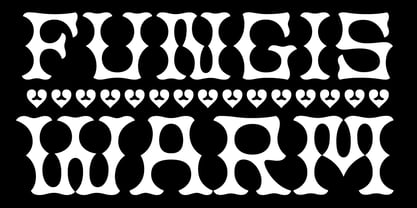

$29.00Years before the "Jet Age", and way before computers and satellite television turned us into jaded "armchair travelers", the ocean voyage aboard giant steamships to distant ports of call beckoned many to travel the Seven Seas. Far away lands had a magic and mysticism to them, for few Americans knew anything about those places unless they read about them in books or saw travelogs at their local theaters. Many songs were written with themes of romantic South Seas travel, and one vintage piece in particular entitled "Down Where the Trade Winds Blow" offered up the hand lettering which served as a model for Sea Cruise JNL. - Fungis by Ivan Petrov,

$30.00Fungis is a somewhat �brother� of Fungia. These two typefaces were conceived simultaneously as an experiment on designing typeface based on natural shapes. In both cases it was mushrooms. Of course the main theme of these typefaces is not mushrooms itself (it was just a start point) but the interaction between form and counterform. In spite of unquestioning individuality the font has some associations with wood typefaces from wild west, typefaces from circus posters of 19th century and even slight feeling of gothic. The font can be useful in different cases: posters, titles, book covers, billboards, street signs, magazine spreads and all situations that demand expressive typography. - Spooky Dracula by Hatftype,

$15.00Spooky Dracula - Drpping Halloween Font is a display font that is inspired by gothic and horror style because its shape is very unique and is perfect for any project that you will use with this theme. Spooky Dracula with opentype features such stylistic alternates, stylistic sets & ligatures good for logotype, poster, badge, book cover, tshirt design, packaging and any more. Features : 1.Uppercase & Lowercase 2.Multilingual support 3.Number 4.Symbol 5.Punctuation. 6.Extra Dingbat 7.Support in Mac and Windows OS -Support in design application (photoshop, illustrator, and more). There it is. I really hope you enjoy it. Comments & likes are always welcome and accepted.